8.14.2024

PBS World on TV.

“They’re showing stingrays now,” he says, in a raspy voice. But he says it.

I left that channel going on his TV when I left here two days ago, a Monday afternoon.

“You’re leaving me?” he asked.

I was. I did. Then I didn’t see him yesterday. No one did, not family. My mom is still sick, too.

This morning I stopped by initially to pick up his dirty clothes. There was a small pile. Then I went to Target for this and that. A small Bluetooth speaker for Brook. Purple. Anniversary gift. Nineteen years.

I picked that up at the service desk, pre-ordered. Then I got a cart and did the rest of the shopping. Five bars of Dr Bronner’s bar soap, a liter of Dr Bronner’s Tea Tree Hemp liquid soap, dog dental chews, three or four pounds of coffee, a boil-at-home/make-your-own bite guard, four tubes of toothpaste, 120 days worth of allergy-stopping nasal spray, and 24 cans of Spindrift. Nearly two hundred bucks, not including the speaker.

But it was good to stock up. We’ll use it all.

Muffled CNA talk through their masks. Details, info, how the cases appeared, how many a day.

The PBS World channel has been on since I left, probably. Animal documentaries. Now the CNAs are talking about ordering N-95 masks on Amazon. Caught off guard, maybe. This is our Late Stage Care infrastructure. And it’s better here than at a lot of other places, if I had to guess.

I pulled the shutters away from the window, to let the light in.

“Oh, I like that,” he says.

With the shutters moved to the side, the view outside is revealed. His window looks into the grassy stretch between A Hall and the long hallway leading past one of the kitchens and down to St. Francis, a.k.a. Assisted Living. Right at the foot of the window, or off to the side a little is the small patio outside the Bird Room. All in all, it’s not a bad view. There is green: the grass, the trees, some bushy grassy landscaping.

I needed the light from outside. If there is anything I need when I am in his room, it’s a floor lamp. There isn’t any overhead lighting. Until the Covid outbreak began, I hadn’t really spent much time in this room. We would always be outside, or in the reading room, or in the Bird Room. Or wheeling around the Shrine/Benedictine grounds whenever and wherever we could.

He says he feels the same; OK.

“I got that Covid, still,” he says, “and pneumonia.”

Peggy comes in. The housekeeper.

“I’m here with my son,” he tells her. “He comes to visit. He’s great.”

She takes the various small cups from the wheeled tray that is either beside or positioned over his bed when he’s in it. Some of the little cups are empty of pills. Some still have a little bit of water in them. Peggy is cleaning the floor. She gets the knife that was on the far side of his bed two days ago.

Mom did talk to one of the nurses. My dad said he thought he had pneumonia when I was here on Monday. That sounded plausible but I had not confirmed it. I don’t know much about pneumonia; never run into it before. Fluid in the lungs.

By text my mom says there’s a floor lamp at Rockingham that might work. My dad starts into a hacking cough. Not too phlegmy? Rough though. He’s still in bed, in his gown. But he’s mostly awake; seems with it.

Peggy cleans the bathroom next. Mom sends another text telling me to open the blinds, if I haven’t yet. Dad rips into another blustery hacking cough.

I want to know what else is going on in the rest of this place. Dammert. Has anyone died recently? The last five days? How bad is this Covid outbreak? How many staff are sick? But I won’t or can’t venture out.

Peggy is mopping the bathroom floor. CNA Taylor is out in the hall. Her and Rachel. That’s a good duo. He’s in good hands. It was bleak in here Monday. Thin. There was a puddle of piss on the floor when I got here, under his wheelchair. His pants were wet. I took it up with a towel.

Taylor checks in. She tells my dad she’s going to get him up when the floor is dry. Peggy is mopping the rest of the room, where the puddle was the other day, then where the cranberry juice was spilled. She mops with a slight bleach solution. Fine. The floor is clean.

Taylor asks him how he feels. He says, “OK.” But you sound terrible, she says. Peggy interjects, “A lot better than he did, though.” She says this as much to me as to anyone, and it makes me feel pretty good. Peggy is really nice. She has red hair. For a while I had forgotten her name.

I’m in my N-95 mask with blue disposable gloves on. My exhalation fogs up my glasses. My hands sweat. I would love a cup of coffee.

The stingray documentary has been over for a while. Now it’s Christianne Amanpour hosting a world news program.

“Is Netanyahu ready for a deal now?” she asks her guest.

I had gotten a book out of my bag, an old book that belonged to my dad called Zen Buddhism. I’ve had it for three years. That’s the last time he was home, in Ludlow, Massachusetts. His cousin Anna now lives in the house he grew up in, what I used to know as my grandpa’s house. His name was the same as mine except for the middle name. His was Beresford, after a Lord in England. Mine is Brian, after my dad.

Anna had a box of his books that had been sitting in the basement of that house, basically forever. I remember her telling me about books of his, boxes. Was I interested in them. I couldn’t really muster the energy to get excited about them. I was sitting out by my great aunt Elsie’s pool enjoying some downtime during what was a challenging trip. It was June 2021. There was a party for Elsie’s birthday. My brother and I had driven my dad out to New England, in what would be his last Buick.

I only took a couple of books from the box Anna brought out to the pool. There was at least one more box I wouldn’t even look at. I regret that now but at least I have one book from that forgotten collection.

It’s a funny little hardcover book with an orange floral print on the jacket. There is such little info about the book on or in the book.

There is no author. A $1.00 cost is listed. It is “A Peter Pauper Press Book.”

Inside, the book is described as “An Introduction to Zen with stories, parables and koan riddles told by the Zen Masters with cuts from Old Chinese Ink Paintings.” The Peter Pauper Press, Mount Vernon, New York. Copyright 1959.

Taylor is getting him changed. Compression socks. Pants. Now the diaper. I don’t know what might be in it. The news shifts its focus to Google’s monopoly power. Taylor is turning him.

“My body,” he groans.

I ask him if he recognizes the book and he says he does.

Then he says, “They got me now.”

“Who is they?” asks Taylor.

“They they they,” he says, “they all.”

“You make it sound like we kidnapped you,” she says.

He doesn’t mean that. It’s figurative. I think he means Death, the Soldiers at The Gate. The forces that bring an end to our lives. They.

But then he starts laughing, and then Taylor starts to laugh.

It takes four rags. They go out into a big bin closed behind a door along the hall. Now she is putting a cream on him. He starts giggling.

“Brian, it’s not funny,” she says, “you laugh at anything.”

Then he starts to wince and to moan.

“Does that hurt?”

“No.”

“Then why are you yelling?”

“Because I do yell.”

She is trying to roll him onto his other side. She asks him to grab onto the railing on the side of the bed.

“Why me, Lord?” he says to no one in particular. It’s one of his sayings. It’s a song by Kris Kristofferson.

It’s cloudy outside. Taylor is taking great care. She’s got a 1-year-old. She was talking about how my dad used to sit in silence in his chair outside his room on A Hall. I remember her trying to cheer him up.

On TV, the news show rolls on. Big Tech, ideology, anti-trust law, 1890, updated since then by the Clayton Act and many others.

My dad asks me when he can get out of his room again. It’s going to be a little while yet, I tell him. Five days. Five more days.

He asks that she put the black shoes on him. He is gentle, funny, kind. It’s the best thing I can say about him and it’s the last thing he is teaching me. If you can’t be kind late in life, then you have nothing. Sick and mean, that’s no way to live, and no way to go.

It’s a long process to get him out of bed. Taylor sunk an hour into getting him cleaned, changed up, and lifted out of bed. He couldn’t stand up so she had to go get the crane. This is a new development ever since the Covid descended upon his body. He’s too heavy to transition from bed to wheelchair. She has to slide the crane harness under him.

It’s the first time I’ve seen him lifted by first this type but then eventually another type of Hoyer. I’m not sure about the spelling. The lift, the crane, the cradle. The harness. Mid-way through, his diaper rips. Taylor has to stop. The harness hurts him. He is shaking. This is not the Hoyer he will eventually be maneuvered with. This one is some sort of halfway Hoyer. There are handles he’s supposed to grab onto, to pull himself up with. But he’s not helping. He is not able to use his legs as a base. His whole lower half is gone. She has to set him back down on the bed. Forces, gravity, the body suspended just wants to go back below.

I helped, barely, get the second diaper on him but we didn’t have it on there quite right. Then, when he is finally transferred to his wheelchair, with new pants on in diaper number two, he pees. Open fountain. Through his pants, through the wheelchair cushion, onto the floor.

And now I understand what was going on here Monday before I walked in. The puddle on the floor. And I have sympathy. And I’m resigned. If he does not get his strength back then…where is this headed? Is he going to be in one of those deck chair things? The bed chairs? They are running out of options. The wolves are at the door. The bear is over the mountain. Taptowne is out of the barn.

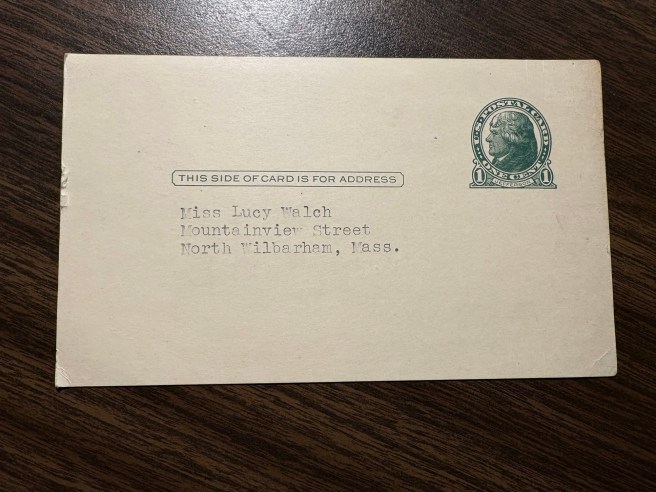

I find an old postcard in the little orange Zen book. It was in there as a bookmark, I guess. The postcard cost one cent, a pre-printed stamp with Jefferson on it. “This side of card for address,” it says.

It’s addressed to a Miss Lucy Welch, Mountainview Street, Wilbraham, Mass.

I turn it over. The writing is by typewriter:

April 8, 1946

Dear Miss Welch,

This is to notify you that your dark glasses are now ready for you. However, the Dr. didn’t remember just what clore colar you wanted the frame died, so if you will stop in, I can die it for you whilr you wait.

Discover more from JBR.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.